ALICE IN WONDERLAND

Anne-Marie Mallik, Wilfred Brambell, Michael Redgrave, Peter sellers, Alan Bennett, John Gielgud & Leo McKern / Music Ravi Shankar / Produced & Directed Jonathan Miller

We’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.

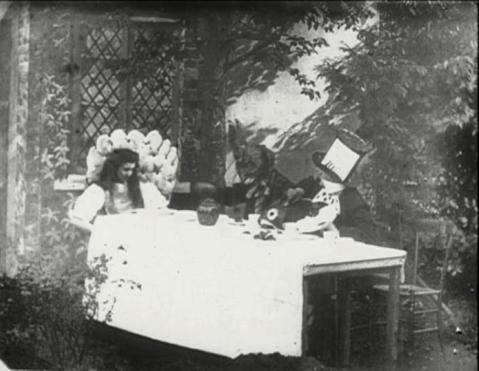

My favourite adaptation of the Alice in Wonderland story by a mile has to be Jonathan Miller’s. If the PreRaphaelites had been able to commit their art to film, it would probably have looked something like this. Shot in sumptuous B&W, and crammed with Victorian oddness, Miller treats the subject matter with an intelligence and wistful beauty that outshines any other Alice adaptation. The social commentary and political satire that characterises Dodgeson/Lewis Carroll’s work is cunningly utilised by Miller to poke holes in both British imperialism and Church & State. There is a certain languid sensuality about this version, but it points more to the loss of childhood, and the unknown burgeoning world of adulthood, rather than anything sordid. ‘But I don’t know who I am..and I don’t like all this growing!’ says Alice. We see the adult world through Alice’s eyes, a world that is baffling and archaic to new fresh eyes. A perfect vehicle for the new 60’s satire at which Miller, Bennett and Cook were at the forefront. Originally intended as a short TV Play, Miller’s enthusiasm expanded the piece into a fully fledged piece of New Wave cinema, complete with a hauntingly cool Ravi Shankar soundtrack, a dream cast of actor heavyweights, and a marvelously petulent Alice in young Anne-Marie Mallik. The actors remain in human form, though still retaining anamalistic characteristics, thus avoiding the need for naff costumes, and rendering the whole affair all the more disturbing. Giddy, strange & hypnotic stuff. Just what Dodgeson intended. Miller payed close attention to Dodgeson’s original illustrations for Alice, embracing their darker mood, unlike those by Tenniel, that we are generally more familiar with.

`I can’t explain myself, I’m afraid, sir’ said Alice, `because I’m not myself, you see.’

The beautifull surreal clarity of the camerawork was achieved by the use of a 9mm wide-angle lens and the artfull work of cameraman Dick Bush. Deftly capturing the ethereal look of Victorian photographic works by Julia Margaret Cameron, Fox Talbot and Dodgeson himself, whilst still maintaining a clarity of image. The wide-angle lens proved most useful to produce the visual distortions required to both create a sense of dreaming vision, and the appearance of a shrunken/enlarged Alice. Objects brought close to the wide-lens distort, and quickly regain clarity as the actor moves away, so a static full body shot set at an angle to the lens warps wildly within the plane of a body. The most exaggerated example can be seen in still below. The list of arcane shooting locations included an old abandoned lunatic asylum, the wilder ouskirts of Oxford, The Sir John Soane Curiocity Museum and a crumbling Donington Castle (complete with hidden swimming pool beneath the floorboards to stand in for ‘The Pool of Tears’).

Anne-Marie Mallik gives us a quite unique Alice, devoid of the usual modern interepretations that ignore the Victorian world from which she sprang, a society where children were seen and not heard. Here, Alice generally speaks only when spoken to, and her opinionated voice reserved for when she thinks out loud, or in the occasional defiant toss of her hair. Miller had few choices available for the role, but was thrilled with Mallik’s performance and what he called her ‘strange joke proof solemnity’, that perfectly captured ‘the melancholy catastrophe of reaching adult life’.

The BBC were not exactly thrilled with the finished product, and complained about it’s length, forcing Miller to lop off half an hour, reducing the run time to 72 minutes. The BBC being the BBC of course, the missing portion was probably recorded over years ago. Peter Cook tried desperately to get copies of his 60’s series ‘Not only but Also’ from the BBC before they wiped them, even offering to buy them new tapes..but no, BBC property is BBC property, and rules is rules. Pete & Dud, Steptoe, Hancock..wiped forever. Considering how expensive BBC DVD’s are these days, the buggers would have made a fortune out of their archives had they not been so reckless.

“Will you walk a little faster?” said a whiting to a snail.

“There’s a porpoise close behind us, and he’s treading on my tail.

See how eagerly the lobsters and the turtles all advance!

They are waiting on the shingle–will you come and join the dance?

Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, will you join the dance?

Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, won’t you join the dance?”

‘There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream, the earth, and every common sight, to me did seem apparelled in celestial light. The glory and the freshness of a dream. It is not now as it hath been of yore; turn wheresoe’er I may, by night or day, the things which I have seen.. I now can see no more.’

WORDSWORTH

______________________________________________________________________________________